“It may happen that this majority of States is a small minority of the people of America; and two thirds of the people of America could not long be persuaded, upon the credit of artificial distinctions and syllogistic subtleties, to submit their interests to the management and disposal of one third.” Alexander Hamilton, Federalist 22, December 14, 1787

“Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests. … And, if a State should provide that the votes of citizens in one part of the State should be given two times, or five times, or 10 times the weight of votes of citizens in another part of the State, it could hardly be contended that the right to vote of those residing in the disfavored areas had not been effectively diluted.” Reynold v Sims

The US Senate has incredible legislative and “advise and consent” powers. It passes bills, but also approves treaties, confirms Cabinet secretaries, Supreme Court justices, judges, and other officials.

It’s 2020, and:

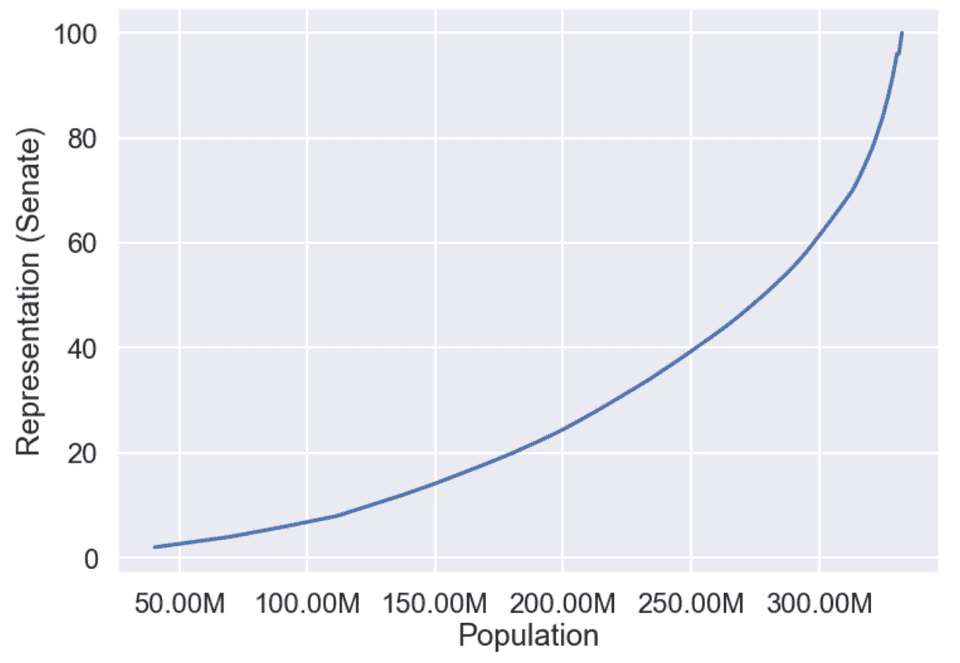

- ~33% of the population lives in just 4 states—California, Texas, Florida, and New York—and is represented by just 8 Senators.

- ~50% of the population is represented by just 18 Senators

- ~70% of the population is represented by just ~1/3 of the Senators

-

10% of the population is distributed across the 19 least populated states, and control 38 Senators.

In 1790, the gap between the smallest and largest states was about 10x. Today, the most populous state, California, is about 70x more populous than the least populous state, Wyoming. A resident of California, New York, Florida, or Texas has no effective impact on the Senate impact, and a resident of a smaller state Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska, the Dakotas, Delaware, Rhode Island, or Maine has a disproportionate impact on the Senate.

While the Electoral College favors smaller states as well, it is still mostly driven by membership in the House of Representatives, which is proportionate to population. That’s unfair—the popular vote loser became president in 2000 and 2016— but it’s far less unfair than the even-more-undemocratic Senate.

The Senate has become the defining slow-motion crisis of American democracy.

- The US Senate could be the most structurally racist institution. In the 1960s, Black people from the South migrated to populous Northern states, eroding their political representation in the Senate. Similarly, recent decades have seen growing Latinx populations in urban areas, primarily located in populous states. As a result, David Leonhardt found that whites have 0.35 Senators per million people, Blacks have 0.26, Asian-Americans 0.25, and Latinos just 0.19.

- Partisanship and rule changes have caused the problem to boil over. According to a 2018 analysis, the Senate has never been as undemocratic as it was in 2017-2018. According to this analysis, “in 2017, for the first time, the Senate’s decisions were often made by a coalition of states representing less than half of the country’s population. The median share of senators supporting passed bills, confirmed judges and agency leaders, and other matters dropped to 58% (the lowest since 1930), with those senators representing just 49.5% of the U.S. population (the lowest ever)!”

It’s time for us to revisit the Connecticut Compromise, the Devil’s Bargain that allowed for the adoption of the Constitution at the expense of a democratic Senate.

What’s the Role of the Senate?

The Senate is a smaller, more deliberative body than the House of Representatives. You have to be 30 years old to run for the Senate, and in 1790, you would have had an average life expectancy of about 45 years. Indeed, “Senator” comes from the Latin word “senex,” which means “senior” or “old man.”

Senators run on staggered 6-year terms, not the 2-year term of the House. That means that their terms exceed presidential terms and—unlike representatives—they don’t have to run in every election. While there are 435 representatives in the House, there are only 100 senators. Unlike members of the House, Senate representatives were meant to be appointed by the state legislatures, a process that changed after the 17th amendment in 1913. This meant that the Senate was meant to be a kind of U.N.-but-with-teeth for 13 (and now 50) coequal sovereigns.

These features—insulation from short-term political pressure and a more selective and deliberative group of representatives—are unrelated to the two-per-state design of the US Senate, and don’t benefit from it.

The Connecticut Compromise was Pragmatic, but Not Wise

Some people defend the Connecticut Compromise as an enduring legacy of founder wisdom. But the Connecticut Compromise wasn’t meant to be wise, it was meant to be pragmatic.

Seven weeks into the Constitutional Convention of 1787, the founders were at an impasse.

Many large states felt that representation should be proportional to population in Congress. As larger states would be contributing more to the treasury and defense, they felt that should have more say.

Smaller states like Delaware and Rhode Island—and representatives from certain larger but slower-growing states like New York (except for Alexander Hamilton, of course)—weren’t having it, and had leverage. These states enjoyed authority and autonomy under the Articles of Confederation. Proportionate representation—plus anticipation of a rapidly growing South and West—would erode their political power.

Connecticut delegates Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth, with the support of Benjamin Franklin, struck a compromise: a bicameral (two-chambered) legislature, with one chamber, the House of Representatives, allocating seats in proportion to population, and the other chamber, the Senate, allocated evenly by state. Benjamin Franklin proposed that the House originate all revenue matters.

Alexander Hamilton hated it. Writing in Federalist 22:

Its operation contradicts the fundamental maxim of republican government, which requires that the sense of the majority should prevail. Sophistry may reply, that sovereigns are equal, and that a majority of the votes of the States will be a majority of confederated America. But this kind of logical legerdemain will never counteract the plain suggestions of justice and common-sense.

Madison, in Federalist 62, didn’t want to defend it:

The equality of representation in the Senate is another point, which, being evidently the result of compromise between the opposite pretensions of the large and the small States, does not call for much discussion.

The decision to allocate Senate seats was a compromise needed to ratify the Constitution and satisfice an existing power structure—nothing more.

This is the Hardest Thing to Change about the Constitution

One possible mechanism of reform is amending the Constitution. Suppose you wanted to change the Senate to allocate seats in proportion to population. Not so fast—Article V of the Constitution writes that:

The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States, shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress; Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of its equal Suffrage in the Senate.

Article V articulates a state right—equal suffrage in the Senate—that cannot be deprived through the Constitutional change process. Put differently: you can change anything in the Constitution (after 1808) through amendments or a convention, but you cannot change this aspect of the Connecticut Compromise.

In practice, even Justice Scalia once remarked that he didn’t see how the Supreme Court could declare a properly proposed and ratified Constitutional amendment unconstitutional. It is unclear how a future Supreme Court might view a dispute around this kind of Constitutional amendment, although any well-written amendment would begin by changing Article V.

Notwithstanding this speed bump, passing constitutional amendments requires the consent of 3/4 of the states, meaning that the 12 least populous states could block any Senate reform amendment.

Finding a Way Out

What does a good solution look like?

An improvement to the representation problem has the following qualities:

- It is legal. In this sense, legal means that it would survive a challenge in the Supreme Court in which the justices were approved by a partisan Senate.

- It preserves the “deliberative” aspects of the Senate.

- It reduces population inequality in the Senate.

- It is politically tractable.

A better solution to this problem has these additional properties:

- New statehood, or reorganized statehood, is incentive-compatible. That means that citizens of prospective new states (Puerto Rico, for instance) should have the opportunity to form a state and be admitted to the Senate without disproportionately diluting power.

- Senate proportionality is robust to population shifts. If Wyoming became a booming population center, then Wyoming should have more Senate representation.

- It decreases wasted votes and reduces the efficiency gap. Conservatives in California and liberals in Texas have important interests, and they deserve a say.

State Swaps

The Constitution didn’t anticipate political parties, and Washington’s farewell address decried them as “likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” In 2020, these parties may be able to usurp power on behalf of the people.

How?

California leans Democratic, but 38% of the population voted for Donald Trump in 2016. It has two Democratic senators.

New York leans Democratic, but 41% of the population voted for Donald Trump in 2016. It has two Democratic senators.

Texas leans red, but similarly, 43% voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016. It has two Republican senators.

Florida is a perennial swing state. 48% voted for Hillary, and it has two Republican Senators.

Political parties may be able to organize around “swapping” permission to break up states for the purposes of the Senate. Suppose, for example, that California and Texas each broke into 3 states for the purpose of reducing inequality in the Senate, but wished to continue to be governed by Sacramento and Austin, respectively. This might be possible depending on how legislators and the Supreme Court understood the word “jurisdiction” in Article IV, Section 3:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

While there may be questions about the Supreme Court’s willingness to read the Constitution to permit this scheme, there is precedent for this kind of swap in the case of new statehood. Between 1812 and 1850, slave states and free states preserved their balance by admitting states in pairs:

| Slave State | Year | Free State | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | 1817 | Indiana | 1816 |

| Alabama | 1819 | Illinois | 1818 |

| Missouri | 1821 | Maine | 1820 |

| Arkansas | 1836 | Michigan | 1837 |

| Florida | 1845 | Iowa | 1846 |

| Texas | 1845 | Wisconsin | 1848 |

Shamelessly replicated from Wikipedia

This plan could globally preserve the balance of political parties in the Senate, while going through the less onerous process of Senate approval and bypassing 3/4 state approval. More representatives across smaller, more evenly sized states could make it easier to pass more durable Constitutional reforms, admit new states like Puerto Rico and DC, and ultimately find a new rule that preserves the will of the people in a deliberative body.

The Long Game: Treating Senate Seats like Congressional Districts

A long-term fix to the Senate might have the following properties:

- Cap the total number of Senators by statute. Dunbar’s Number is a useful heuristic. The Senate could include between 100 and 150 members.

- Use fair, efficiency gap-minimizing techniques to allocate Senate districts. Today, a Senate district is a state. In the future, there may be Senators representing multiple states, parts of states, or factions of multiple states—fully divorcing the Senate from states.

- To preserve the founder intent of having 2 senators for each region, set 2 senators for each region.

- In the event that a senator can no longer serve the remainder of their term, a replacement could be determined by the other senator, rather than the state government, until a special election can be held.

- The Electoral College is replaced with a popular vote.

Each step above could make the the next step possible, and ultimately creeate a more equitable, representative US Congress. Can we get there? Maybe, but it’s not clear what crisis or compromise would start us down this road.

A few possibilities are:

- A major political realignment. The growth of urban centers in Texas could make it a Democratic state permanently, which would affect the presidential electoral balance far more dramatically than Senate balance. This could create a path to compromise.

- Civil protest. A controversial withholding of a bill or political appointment could cause protests in large states. Protesters could coalesce around their Senate disenfranchisement and demand political change.

City living is greener, healthier, and economically more vibrant than alternatives, and today, 83% of the U.S. population (and growing!) lives in urban areas. As more people choose to live in large cities, we risk an increasingly unequal Senate. As someone who lives in a city in a populous state, I hope a democratic Senate becomes a possibility in my lifetime.