How to Kill Your Company by Making Too Much Money

A profitable, high-growth company can grow to death. You can be unit profitable and sales can be through the roof and you can be dead.

Imagine that you’re an entrepreneur starting a beverage company. After selling at small retailers, you strike gold and sign a huge contract with Walmart. Since you’re a newer, smaller manufacturer, you only get 90 day terms—meaning that Walmart will only pay you 90 days after you fulfill the order. You don’t have to pay your suppliers for 30 days, so you essentially have 60 days of cash you need to find so you can pay your suppliers, manufacture your product, get your inventory to Walmart, and later, get paid.

If you have unlimited cash: no problem, congratulations, you can stop reading here.

If you don’t have unlimited cash: your profitable, high-growth startup will stop growing… unless you can find the cash to pay your suppliers before Walmart pays you. If you agree to the Walmart deal and aren’t able to secure the working capital to cover your inventory expenses, you’re in trouble. If you order extra inventory and the Walmart deal doesn’t go through, you’re in trouble. If you place the order and for some reason Walmart doesn’t sell your product and won’t pay you, you’re in trouble.

Maybe you started with 1,000 cases of your beverage with great margins, but the product flew off the shelves so quickly that Walmart quickly ordered 10,000 cases. Now you have 1,000 cases of profit, but need to find 10,000 cases of cash. And you’re in trouble.

This is the meaning of cash is king. Cash flow is the lifeblood of any company. While a company have phenomenal profitability and stellar growth, if it runs out of cash, it’s game over.

Let’s understand the biggest drivers of cash flow and what they mean.

The Physics of Cash Flow: Profitability, Growth, and “Asset Intensity”

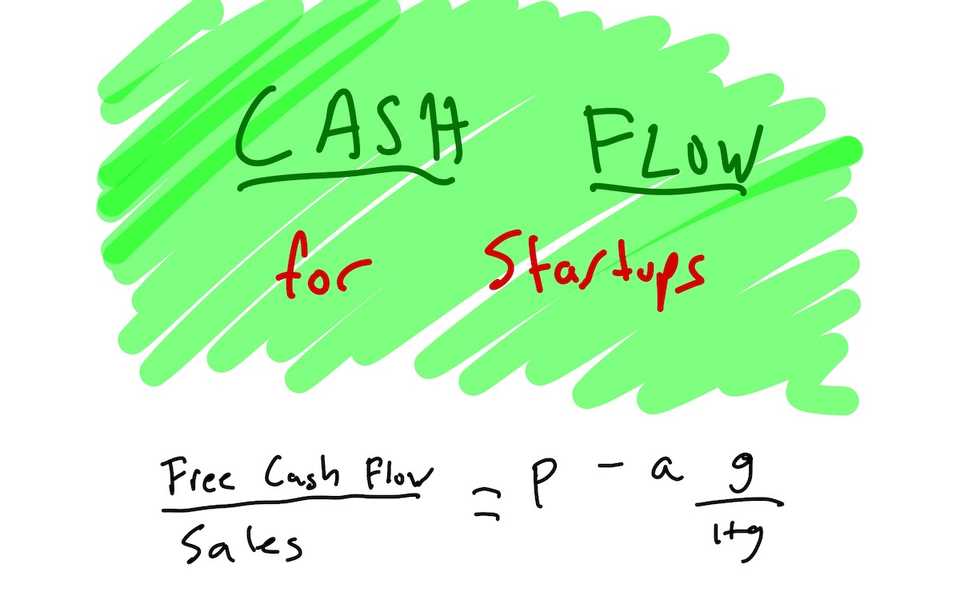

The traditional formula for free cash flow is messy, complicated, and unintuitive:

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes [EBIT]

Less Tax Exposure [corporate tax rate (t) times EBIT]

Plus Depreciation [D]

Less Change in Net Operating Working Capital [NOWC]

Less Capital Expenditures [CX]

Less Change in Net Operating Other Long Term Assets [NOOLTA]If we make simplifying assuptions that (1) sales drive all other operating variables and (2) growth, profitability, and asset intensity don’t change, then we get this beautiful, simple model of free cash flow:

where

Most people have heard of profitability and growth.

Profitability is how much of a dollar that you sell you get to keep, before interest and after taxes. The higher the profitability, the more of every dollar you get to keep. With low profitability, less cash available to reinvest in the business or distribute to shareholders or bondholders.

Growth is a percentage measure of your sales tomorrow relative to your sales today. If you’re profitable and growing, then you’ll have more cash available in the long run.

It’s that in the long run that makes this tricky. Suppose you offer a product for $20/month, and it costs you $100 to win the sale. An additional sale today will tie up $80, assuming you’re paid the first $20 at the beginning of the month. If you only have $800 in cash, you can make 10 profitable sales…and immediately be out of business.

That’s where the concept of asset intensity comes in. Asset intensity is the ratio between the net operating assets (NOA)—the assets needed to generate the sale—and sales. To understand it a different way, ask yourself: “how much more in assets do I need to make an additional sale?” Put a different way: “for me to make an additional sale today, does it tie up cash, or does it free up cash?”

Asset Intensity: Does it Tie Up Cash or Free Up Cash?

If it ties up cash, it has a positive asset intensity. If it frees up cash, it has a negative asset intensity. And if it cash neutral, then it would have an asset intensity of 0.

| Asset Intensity | Example Business | Why | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive or Neutral | Most businesses—retail, hotels, restaurants, manufacturing, etc. | Businesses where accounts receivable are larger than or comparable to accounts payable in most periods. | ||

| Negative | SaaS businesses driven by organic growth, insurance, consulting firms, Blue Nile (they sell inventory without owning it) | Services where you pay today and get your product or service tomorrow, or where you have more time to pay your suppliers than your customers have to pay you. | ||

Negative Asset Intensity and Deferred Revenue

How do we free up cash?

Suppose Dropbox wins a customer that comes it organically (that is, without paid marketing). The customer is interested and immediately signs up for a month-to-month plan at $10/month.

At the beginning of the month, Dropbox has recognized $10 in revenue because they have received $10 for services offered. Dropbox can’t actually realize that revenue until they have delivered the service. That means that, instead of booking the full amount as revenue, they book it as deferred revenue—that is, revenue that is deferred until the service is delivered.

So the deal a customer makes with Dropbox: I’ll give you money today, and you don’t have to provide the full service I paid you for until tomorrow. What does that do to Dropbox’s balance sheet? At any given moment, they have a full extra month of cash—for free.

Suppose the same customers was willing to accept 2 months of service for free if they paid for a year in advance—that is, $100 /year upfront, instead of $120 /year month-to-month. In a year, Dropbox is giving up $20 in profit…but gets to defer a full year of revenue, and invest it in whatever they want. If it costs Dropbox $100 to acquire a new customer, the upfront cash from their first customer just bought them a whole second customer.

You can learn more about the psychology of upfront pricing (here)[/posts/psychology-of-upfront-pricing/].

Tying Cash Flow to CAC, LTV, Churn, and Payback Period

A lot of SaaS investors give advice like this:

| Investor Metric | VC Advice (SaaS) | Cash Flow Metric |

|---|---|---|

| LTV:CAC | 3:1 Good; 5:1 Great | Profitability |

| Payback Period | 9 months good; 6 months great | Asset Intesity |

| Growth | 10% month-over-month good; 15% month-over-month great | Growth |

Lo and behold, this advice maps beautifully onto our cash flow metrics!

Tying It All Together

- Cash is king. Startup equity isn’t accepted at grocery stores.

- You can grow to death. You can sell a product that is profitable and high-growth.

- Profitability, growth, and asset intensity are the three drivers of cash flow.

- Asset intensity. Some operations tie up cash as they grow, and others free up cash as they grow. Ideally, you want to free up cash as you grow. The cheapest dollar of working capital you’ll ever get is the one you earn from an upfront customer.

- Relationship to VC metrics. You can think of the cash flow metrics as analogues to LTV:CAC, payback period, and growth.