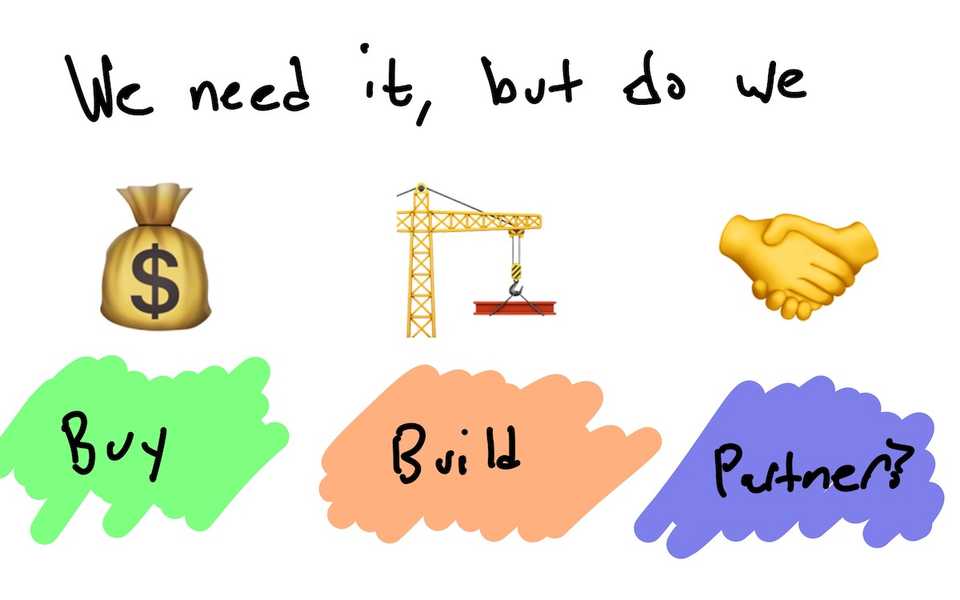

Buy, Build, or Partner: Asset Specificity, Uncertainty, Frequency

The Big Idea

Why do firms—and employment—exist? Couldn’t a founder just contract out every single job?

Why do some firms buy other firms, or build otherwise available functionality inside of the firm? Couldn’t they just license everything?

Does that exciting new feature or capability actually belong in the business, or would it be better off outside?

There are plenty of “buy, build, or partner” scenarios like this. Here’s how to think about them.

The Heuristic

Three factors drive whether you should buy, partner/license, or build.

Asset Specificity

Asset specificity is the single most important driver of vertical integration. It refers to the extent to which assets are useful for fulfilling a contractual obligation, but not very useful otherwise.

Assets may be specific if there are:

- Few alternative buyers or sellers. Suppose a supplier has one credible customer, and that customer has one credible vendor. This could be because they are located close to each other, or located close to a resource they both need, or because they rely on special-purpose equipment or skills. It may make sense for these firms to vertically integrate.

- Trust issues, including sharing secrets. For instance, the whole operation would be better off if we could share secrets, but we can’t as long as we are separate firms.

- Internal pricing. If some assets are hard to price, vertical integration may make sense since these issues are reduced.

- Time-coordination pressures. If latency or coordination time is an important factor, vertical integration may make sense.

Pixar could have distributed its films with anyone, but Disney had the unique ability to integrate Pixar properties into parks, merchandise, and more.

Frequency

If you drink a lot of milk, buy the cow. Frequent transactions suggest vertical integration because of the setup cost of each transaction, and due to trust effects like reputation.

Suppose you work with a talented freelance designer. If you work with them frequently enough because they do excellent work, it may make sense to bring them into the firm because you’ve built trust and because the setup cost of negotiating each individual piece may be high.

Before acquisition, every time Pixar released a new film, they would have to negotiate a new contract with Disney (or potentially another studio). After vertical integration, these trust and setup issues went away because they were inside of the same company.

Uncertainty or Contingency

If the future is uncertain, or if there are a lot of contingencies, it makes sense to vertically integrate. Hiring a Lyft driver is fairly straightforward: get someone from A to B with reasonable assurances of safety and cleanliness. By contrast, “go solve this complex product challenge and persuade the team to do the right work” is a much more uncertain challenge. Planning and write that many “if A, then B” clauses into a contract would be prohibitively complex.

Contracts between Pixar and Disney likely grew in length over time as they learned more about contingencies that can come up with animated films.

Where You Can Use It

Jobs: Do we hire for this role, do we contract it, or do we try to automate it away?

If you can contract for a job, that’s often a good start. If the job is extremely specific, uncertain, or high-volume, hire. If you can’t hire or contract—perhaps the need is extremely specific to inside of your firm—train.

In logistics: FedEx relies on contractors for delivery, while UPS employs its drivers.

Assets or Features: Do you build a certain asset, do you use a vendor, or do you buy the vendor?

In tech: Should Apple buy a popular app, replicate its functionality as a first-party app, or should it do nothing and let it succeed in the marketplace?

In logistics: Even though FedEx contracts its drivers, FedEx stores are corporate-owned while UPS Stores are franchised.